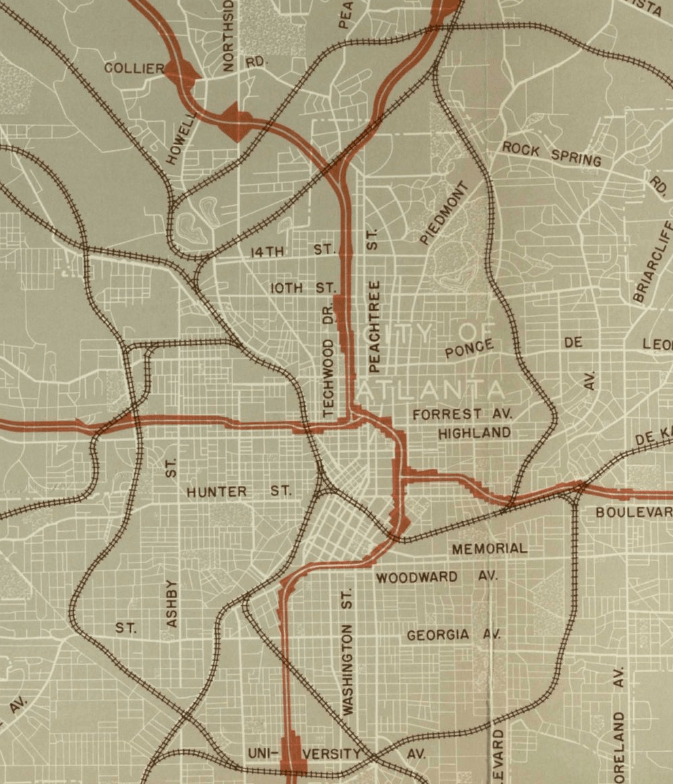

In the mid 1940s, Atlanta was struggling. The city had grown far faster than its infrastructure could handle; a booming population, the rise of affordable personal automobiles, and industrial might were all befalling the city faster than Atlanta’s roads could keep up. And though the city had an expansive streetcar network at the time, that alone wasn’t going to keep the city afloat.

Much like lobotomies, there was a solution to this problem that cities all over the United States (and the world, to be fair) were applying: carving up their downtowns and adding highways, many of which would be interstates by the time they were completed, right through the city center. This is a horrendous method of city design in so many ways, not the least of which is slashing the city in half to make way for drivers, the majority of which pass through, not into, the city. Even though this would have a profoundly negative effect on the city of Atlanta for the rest of its history, the popular personal automobile and highway technologies were relatively new, and so it is maybe understandable that city planners would think this was the best way to develop their cities in the new post-war world.

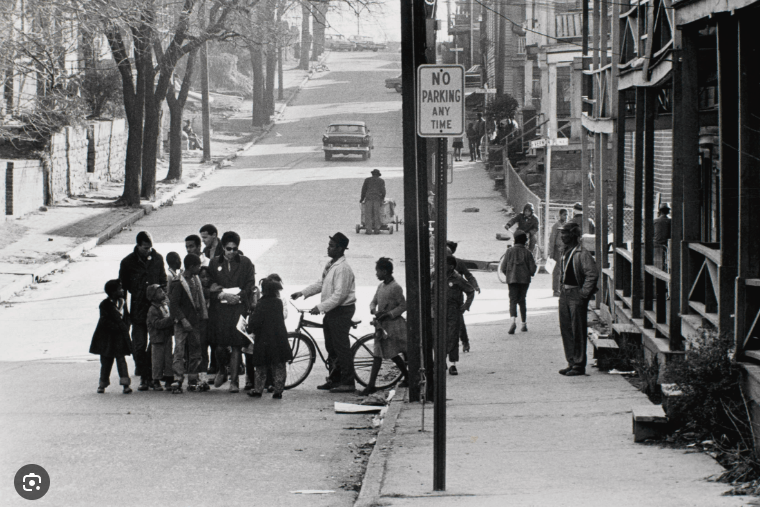

What is most certainly not understandable is the massive number of people that were displaced by this project. Massive swaths of land in the middle of a city don’t just appear from thin air, and the designers of the highways knew exactly where to aim: black neighborhoods. And in a pre-Civil Rights era, there was nothing any of them could do about it. Of particular note for the sake of today’s topic is Buttermilk Bottom, the neighborhood sitting between what is now Downtown and Midtown, that was completely erased from the map in order to build the freeway. Buttermilk Bottom, like most of Atlanta’s black neighborhoods, was in dire need of infrastructure improvements, but the city forwent improving these districts in favor of demolishing them entirely.

Let me put in a disclaimer before we move on: I am absolutely not suggesting that The Stitch will somehow make up for the razing of Buttermilk Bottom or other neighborhoods. Those neighborhoods are gone, the people displaced for decades, and the new project doesn’t exactly give back to Atlanta’s black population in any special way; it is merely a development like any other. I believe the city of Atlanta as a whole, including its black population, will benefit from The Stitch, but it aggravates me when it is marketed as somehow giving back to those Buttermilk Bottom roots. But this history is incredibly necessary, and needs to be told – it will forever be the legacy of this area, and we cannot let it be forgotten.

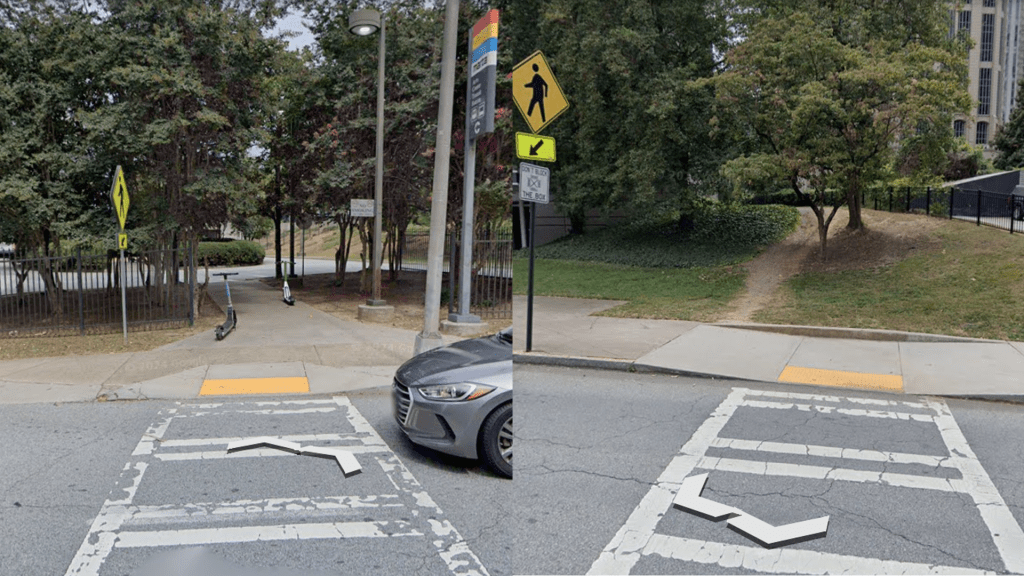

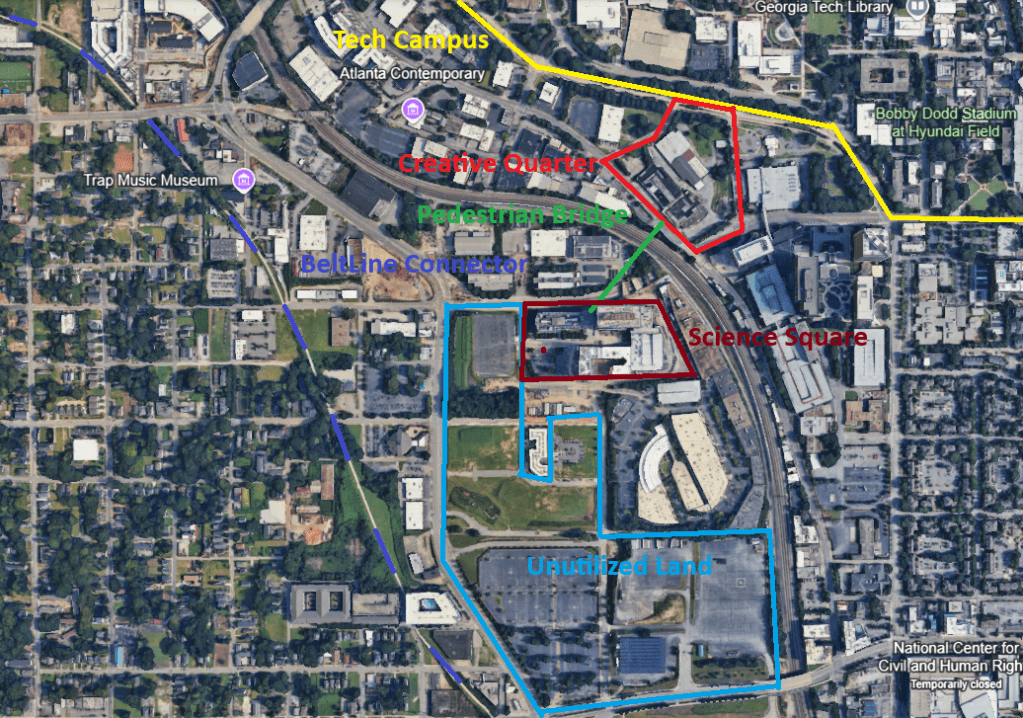

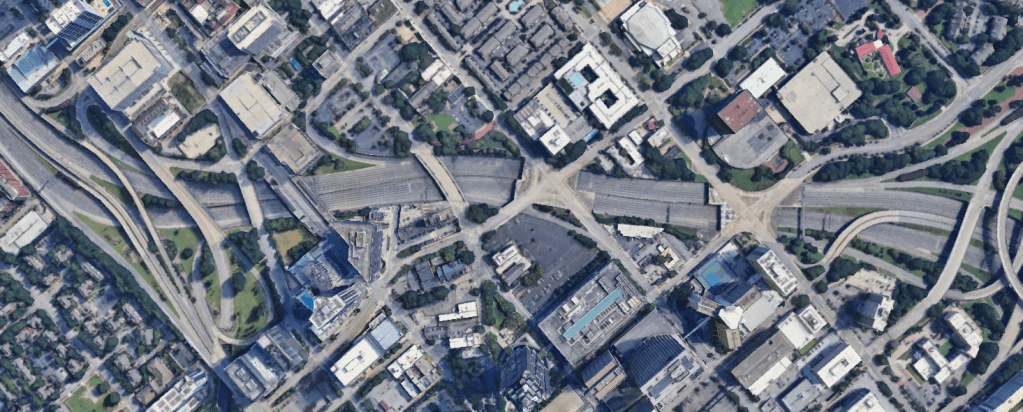

Fast forward to today, the Connector has done a lot of damage to traffic flow in the city – there’s a reason Atlanta is notorious for its terrible traffic. And while the entire Connector has made Atlanta infamous for terrible traffic, one particular stretch stands out as particularly destructive: where the Connector crosses from the West side of Midtown to the East side of Downtown. This section of car sewer literally cuts the city in half, and the effects are much more than visual. Midtown has been thriving for the past couple of decades; the transformation from empty lots and 1 or 2 story buildings to a high-rise filled mixed-use urban haven has been staggering. But on the other side of the Connector, the love hasn’t been spread.

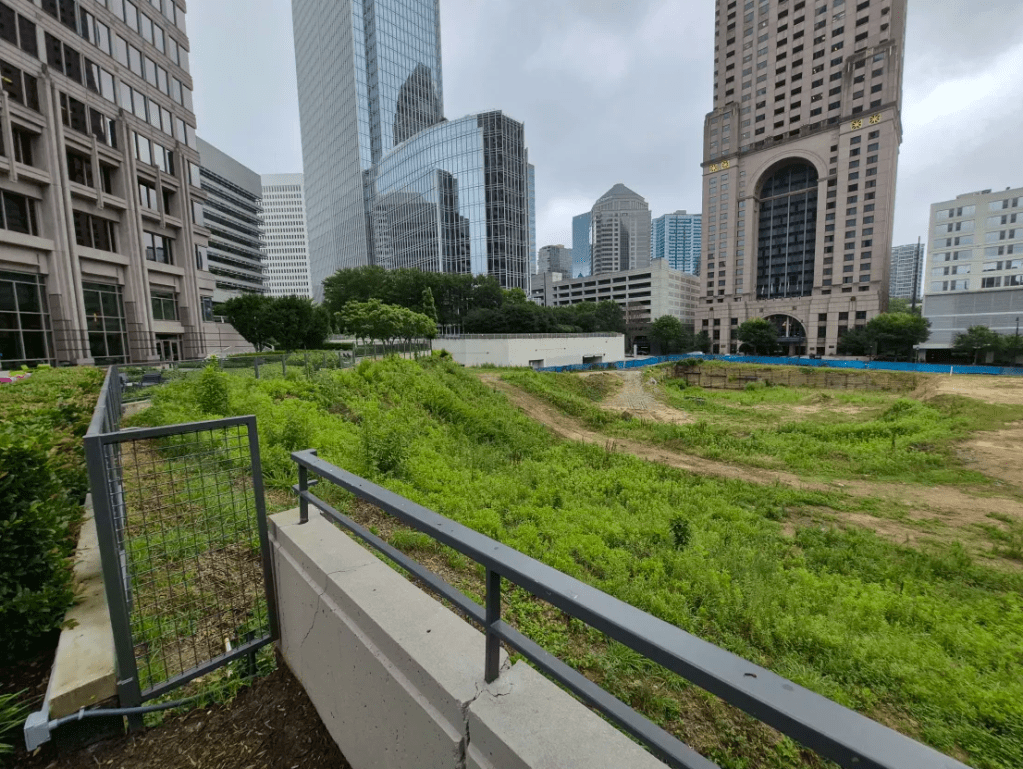

Downtown Atlanta’s story has been a bit different to Midtown’s in the past few decades. There certainly hasn’t been no development – the City of Atlanta and Georgia State University have been revitalizing where they can – but the difference is clear. Private development has, until recently, been much slower, the area is still riddled with parking lots, and (especially in South Downtown) abandoned, shuttered buildings aren’t an uncommon sight. There are obviously a variety of reasons for this, and it’s beginning to change with public and private projects such as Centennial Yards and Georgia State’s Blue Line, but it is undeniable that the damn interstate creates a literal barrier between the success of the North and the stagnation of the South.

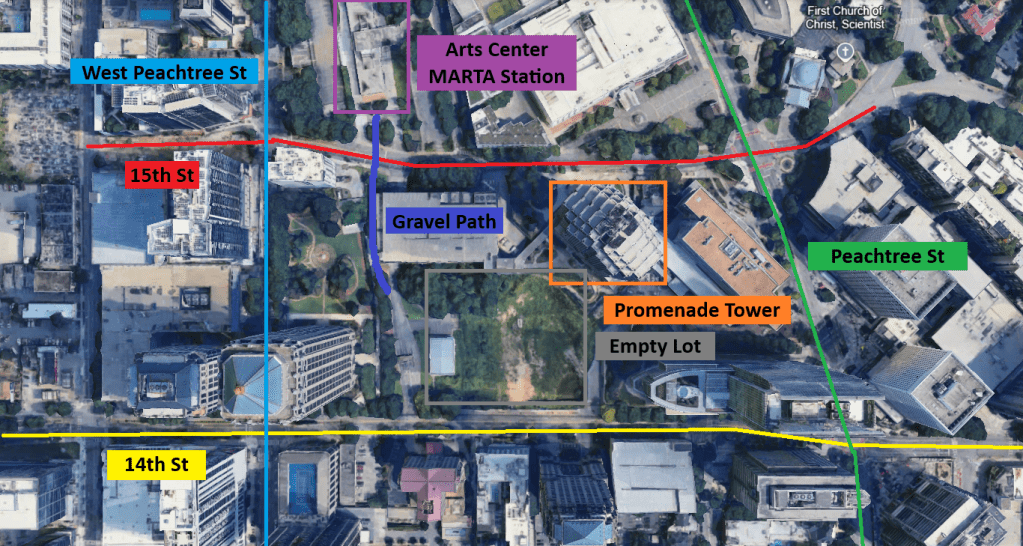

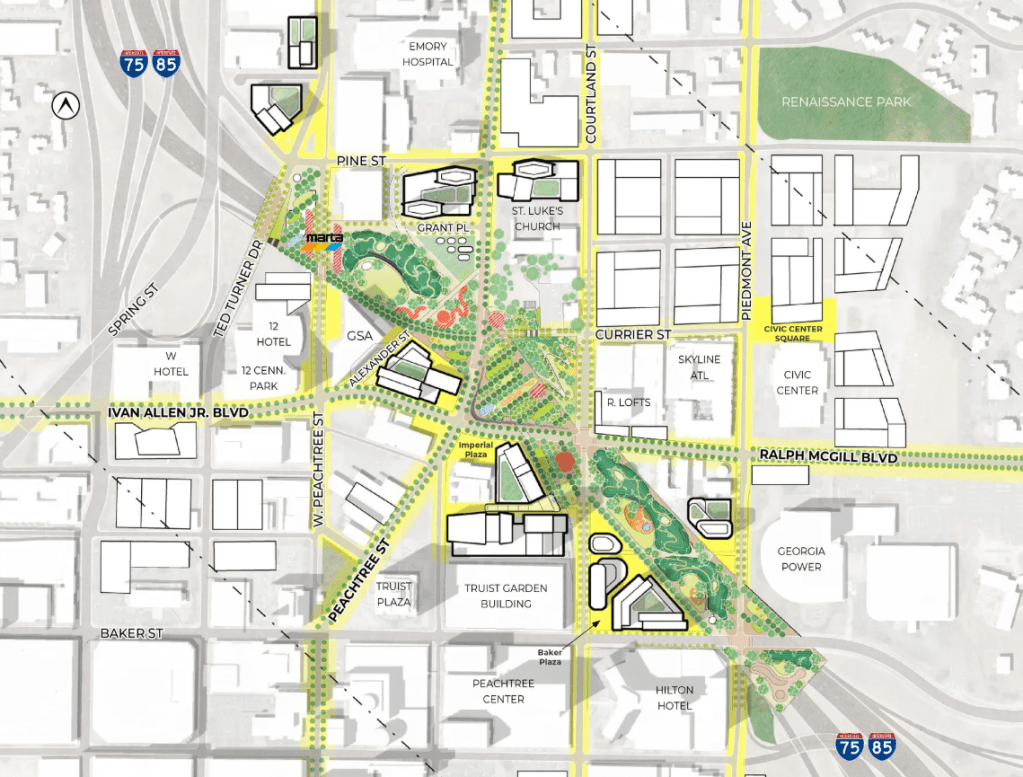

Enter: The Stitch – And the name couldn’t be more fitting. The Stitch is a highway cap project that aims to erase the separation between Downtown and Midtown by creating several acres of land on top of the Connector. This land will then be developed with parks, offices, and most importantly, residential – a key component that Downtown is sorely lacking. Equally important are plans for affordable housing, better infrastructure for pedestrians and bikes, and integrating (and redeveloping) Civic Center MARTA Station into a vibrant community.

The Stitch has its detractors though – most agree that the project would benefit the surrounding area from a development perspective, but there are questions of equity and gentrification. Midtown’s development has been rapid, but it has also been very expensive, and is mainly focused around higher end apartments and condos, as well as offices. While The Stitch has affordable housing goals, there are several projects around Atlanta that have set such goals in the past and failed to meet them. And then there is the simple element of money; is this really the best use of over $200m of federal funds? Where else could this money go? Perhaps it would be better spent on infrastructure in West and South Atlanta, where demographics are poorer, infrastructure is worse, and needs such as transit, food access, and safety are more pressing.

And, oh no – did you hear that? Over $200m in federal funds. That doesn’t bode well for a project that’s only just getting rolling in year one of president Trump’s DOGE-driven administration. Atlanta is notorious for spending many years and massive amounts of money on studies just to never move forward with projects (see the recently cancelled Eastside Streetcar expansion). Federal funding is supposedly already secure, but is that really the case? It’s hard to tell what the future of this project is at the moment.

Personally, I hope the project comes to fruition. Despite gentrification concerns, I think development in Downtown Atlanta is inevitable. And while I understand that money could and probably should go to other parts of the city that need it more, the simple truth is that big flashy projects like The Stitch are more likely to earn federal grants than smaller projects, and we need to take advantage of opportunities as they come. The idea is, as The Stitch and other developments around Atlanta gain traction, they will spread development to other parts of the city that need it more. We are already seeing this happen Downtown, and hopes are high at the moment that South Downtown will see a similar revitalization in the coming years. The benefits to the economy, as well as quality of life for those who live in the area, will also have a positive impact on the city’s ability to improve areas in need.

The damage of the connector is already done, and it can’t be fixed. Traffic infestation will forever be a part of Atlanta’s legacy, and the thousands of people it displaced will never get their land back. But as Atlanta’s resident’s we have a responsibility to ensure that projects like The Stitch doesn’t just become another skyline project for fat cat developers. We need to fight for issues in areas of the city that need it as well. And there’s no guarantee that either of those things will happen. But if we can use The Stitch as a catalyst for development, improvement, and good urban design, I think Atlanta as a whole will benefit, and maybe heal some of the scars that as of now remain completely exposed. And if we can get this project rolling, get it filled with affordable housing and parks and transit developments, maybe we can finally rectify some of the urban planning mistakes of our beautiful city’s past.